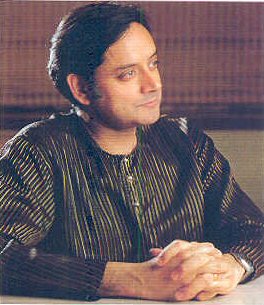

The results of the second United Nations straw poll to select a successor to UN Chief Kofi Annan are out. And the story is almost repeating itself. South Korean Foreign Minister Ban Ki-Moon has emerged as the front-runner, with the UN Under Secretary-General for Public Affairs, India's hope - Shashi Tharoor following a close second.

Will the results, when they finally emerge, return the diplomat turned author to the world of literature? That was one of the many issues that cropped up in my wide-ranging conversation with Shashi Tharoor during his whistle stop tour to South-East Asia, which expectedly was in a bid to lend a shot in the arm to his UN campaign. Singapore was one of his chosen stops and while he plugged his UN bid with ease, I wasn't entirely sure if he'd be in the frame to switch to author mode.

The journalist in me told me the worst I could hear was a tough 'No', so it was entirely worth taking my chances.

Those looked rather bright when the ink was about to touch the paper. They say you can tell a lot about an author by the way he signs your book. The minute Tharoor had inked in

'For The India We Share' in my copy of 'India: From Midnight to Millennium', I knew I had a chance, notwithstanding the rather stand-offish PR person who gave me that look that meant - don't even try, you know it can't be done.

While walking him to the set, I mentioned I worked on a book segment as well and whether he'd like to talk about his life as an author. 'Yes' came the reply. Knowing that we had cameras round the bend, I took the next chance,

"So can we do it after your live interview?"

"Sure" he said....

Yes, it turned out to be as simple as that. I never go into my interviews without all my research done (book festival organisers in this part of the world would vouch for that!), though in this case, I barely had time to get the books in the shot and get cracking.... Here's how it all began:

Q : Dr Tharoor, thank you so much for your time. I'm going to start with 'Riot' - a novel that touched me deeply. You told it through several memorable characters. How did these characters play in your head and how hard was it to feel that you were convincingly getting into the heads and voices of these different people?A : You're right, its a novel about multiple versions of reality, about what the nature of truth is and how people have different perceptions of the truth both for the past and for the future, the way in which people unfortunately use history as a battle axe to fight out the battles of today. Given all of that, I felt it was important to not have one particular voice because one voice assumes one view of reality. I felt with a novel like this, everyone's view, which is of course, completely mutually contradictory has to be given its ones expression. So I came up with this idea of writing the novel through the voices of all these different characters. It was a challenge for me as a writer, both in terms of style because the voices had to sound sufficiently different that the reader would instinctively know who was speaking as it were but equally you had to get into the head to imagine the voice of the character. To give you a simple example, when I described this fictional town in 'Riot', which is a town like many towns that I've seen growing up in India, I had to do it in the voice of this lady who is a middle-aged educated American white middle class English Professor. So I not only had to imagine the town, I had to ask myself what would a character like her notice about a town like this, from her foreign perspective. That was part of the challenge, but in fact in many ways it made it for me a far more interesting experience as a writer to try and re-imagine as it were things that I would have only seen from my perspective.

Q : But why pick an American aid worker who really doesn't belong to any side in the riot?A: It's a novel about collisions of various sorts. There are collisions of different duelling histories, collisions of different views of modernity. It's deliberate that you have an American Coca-Cola executive, in the days when India was protectionist about Coke coming in to introduce his product in this rather closed market. That meant cultural penetration into a society, which was somewhat closed. There are also collisions among individuals. The American aid worker is somebody who comes to do good but comes with a colossal amount of her own cultural baggage without her own full understanding of the society that she is in her naive and idealistic way trying to change for the better. So she is ultimately defeated by her incomprehension. That had to a require a foreign character and to me an American character made the most sense for the various other things that happened in the novel as well. Doing that meant that these collisions between various ideas and various ways of looking at the world came into full play. If you recall, one of the things I have in the book is her father, the Coca-Cola executive saying

"you people have too much history. I don't care about your past, it's your future that I want to be a part of." That's an attitude which in some ways, I think we are seeing more of in India these days. The novel is set in 1989, if you were to write a novel like this about India in 2006, I think you'll have a lot more characters who are as impatient about the future as the American characters in my novel. So it is a portrait of a particular time.

Q : Speaking of India, I visited Punjab last year. After almost ten years, I went on a road-trip from Amritsar to Chandigarh. When I came back, I told my friends here how there were no villages left in Punjab. Almost every little town was on the cusp of transforming into a booming metropolis. Shopping malls, bustling markets - almost all the consumerist trappings were there. The changes were fascinating. You've tracked India from 'Midnight to Millennium', captured various facets of our fascinating country. What is it that strikes you most about all these changes transforming India right now?A: You are absolutely right about the changes, Deepika. I'm always hesitant to pick any one thing about a country as large and complex about India. But my short answer would be, there's an extra-ordinary sense of optimism about the future. Whenever you meet Indians today, pretty much from all backgrounds, I'm not just referring to the educated classes, but people who are domestic servants, people who are drivers, workers, shop keepers - when I speak to them I see an absolute conviction that life will be better for their kids and that their own lives will be better than their parents lives. That's true across the board in India, there is that sense of optimism that opportunities are much greater than they've ever been. Its a fascinating thing and it's exactly the opposite of what I knew when I was growing up in India. When I used to meet people of my parents generation who would tell me I would not have in my 20's what they used to be able to have because of the way the country had gone in terms of economic choices and other things. It's been a complete reversal and that I think is the most encouraging thing.

Q : Moving on, why a book based on the great Indian epic 'The Mahabharata' on the one hand and Bollywood movies 'Show Business' on the other? Two entirely disparate fields, what drew you to these?A : Well, each of my books is very unlike the next. I hope you'll agree that though they are by and large unified by an interest in India, they are completely different ways of looking at the Indian experience. The novel, we just talked about

'The Riot' is a fairly serious look at a powerful and painful reality whereas

'The Great Indian Novel' and

'Show Business' are both satires. 'The Great Indian Novel' was an attempt to really re-imagine the entire political history of 20th century India through a reinterpretation and re-invention of characters, episodes, philosophies from 'The Mahabharata'. That was my first novel and I pretty much threw everything into it as it were.

Whereas 'Show Business' is simultaneously about the movies, about politics and about a certain view of religion - all three of which are meant to be 'Show Business' not just Bollywood. But it's using Bollywood in a sense or cinema as a metaphor for exploring the Indian condition. The fact is both novels are united by the fact that they are satires. They are also united by the fact that they are about the kinds of stories a society tells about itself. What, in the case of the epic, were the lessons of our legends. 'Mahabharata' is part of the popular consciousness of most Indians and at the same time the legends of the nationalist movement which again is part of the received wisdom about the political heritage of India. So I took the two, conflated them and played an unfamiliar tune by striking familiar chords.

With 'Show Business', so many people go to our movies. We make five times the number of movies than Hollywood does, we sell possibly ten times the number of tickets. Of course, much cheaper tickets. So there's this huge film industry, which particularly in a country which at that time was more than 50% illiterate, cinema became and was the principal fictional vehicle in the country. The transmission of the fictional experience was through cinema rather than through novels, books and stories, largely because so many people couldn't read. So I asked myself what are the kinds of stories that our cinema is telling our people about ourselves? What are these escapist fantasies meant to reveal and again what are the lives of those who produce these fantasies. So its a novel that looks at all of that and in that process I hope tries to illuminate some aspect of Indian reality. One of my favourite reviews really of that book was in The Sunday Times of London, which said

"this is an enormously funny and enjoyable book without for a moment being frivolous". That's precisely the point I wanted to convey - that you can make some very serious points, have some very serious insights into your society while writing it in a rollicking and entertaining manner.

Q : Moving on, how did your recent collection of essays 'Bookless in Baghdad' happen?A : It's a collection of literary essays published around the world in the last couple of years. Unfortunately, I've had very little time to pen something new. One of the 40 essays, from which the book derives its title happens to be about my visit to Iraq at the time of the peak of the sanctions, when I found the middle class selling their own books on the sidewalks in order to survive. So it's a literary rumination about the place of literature in people's lives using that Iraqi example. But a lot of the other essays are Indian type reflections as it were about Indian writers, about the popularity of P G Wodehouse in India, on why Indians don't read Pushkin, on why I don't like Nirad Chaudhari (laughs)... so you get the drift. It's very much a thinking aloud for the reflective and I hope the interested reader about the joys of reading and writing.

Q : A lot of writers I interview these days who are Indian but live outside of India, don't want to be called Indian writers. Do you have any problems with that label?A : I have absolutely no hang ups about that. In fact, there is at least one writer I can think of who says she is an American writer of Bengali origin, I'm not at like that at all. I'm an Indian writer, I've never had any other passport. I happen to live in New York because that's where my job places me, but I lived in Singapore, I lived in Geneva and tomorrow I might be sent off to Timbuktu for all you know. But the fact is, I'd still be an Indian wherever I go. I haven't made the leap of the imagination that immigration entails, I see myself very much as a writer with Indian concerns, Indian sensibilities and a lot of my own writing is in any case a self-interrogation about what India means to me and therefore, through me to other people as well.

Q : I know, you are running out of time, but I have to ask you this. Most of us grapple with 9-5 jobs or in my case a 3am to noon job. You have a high-profile and demanding job at the UN, how do you even find time to pen your thoughts?A : It's actually worse at the UN. It's often a 9am-8pm job, never quite 9-5, often the hours are much longer than that. As I've risen up the structure of the UN, my social obligations have also multiplied. Often a lot of evenings are gone to dinners and other events. As a result, my time for writing has indeed shrunk over the years.

It's worse when it comes to writing fiction because for that you need not just the time, you need the space inside your head, the space in which you can create an alternative moral universe populated with people, characters, episodes and situations that are as real to you as the people you meet in your daily lives. That obviously has become much more difficult now.

In the old days, I'd write pretty much every evening, every weekend or when I was on holiday, I would ensure some of my time would be spent on writing. I would even write on planes, cars - pretty much wherever or whenever I could. Some of that has subsidised. But who knows. I am currently a candidate to be Secretary General of the United Nations. It's entirely possible that the Security Council will vote to return me to the world of literature, in which case I might be answering your question differently next year, Deepika.

- Hopefully, you'll get the best of both worlds Dr Tharoor. Thank you so much for your time.